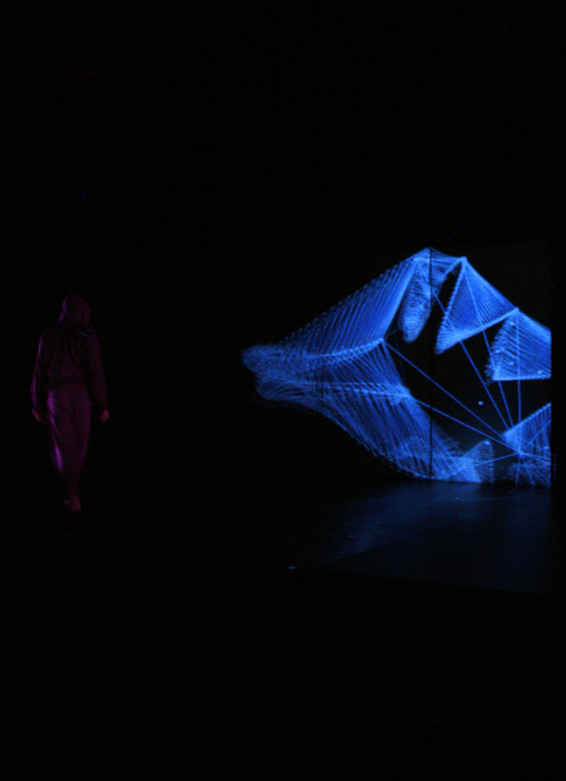

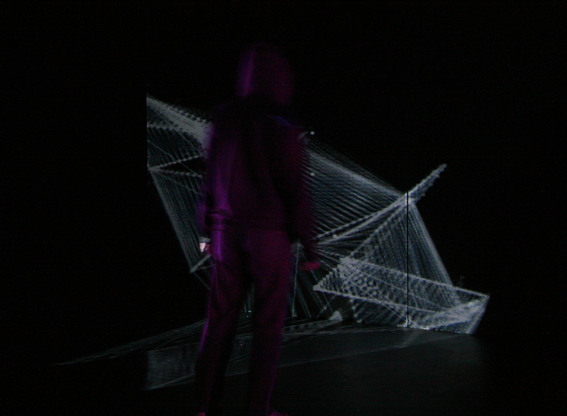

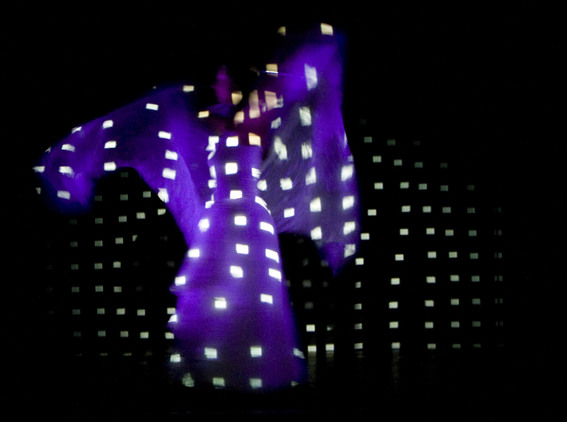

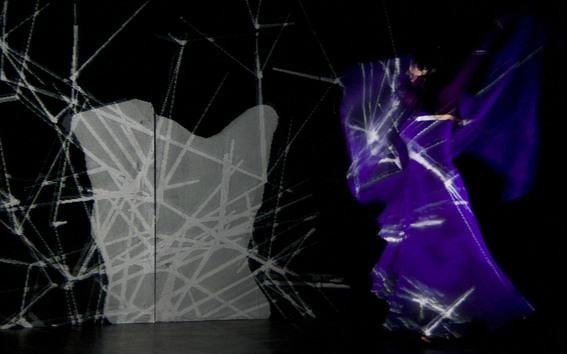

Jessica Millman in scene 1

Jessica Millman in scene 1The

following words and images document the September 2010 development of

feedback and associated work-in-progress showings. Much of this

document is written in present tense as feedback is still

under development and will undergo significant change before it

reaches a final incarnation.

I

originally created feedback as an extension of my lighting

design practice. It has evolved into something much more due to the

contributions of my collaborators:

Composers:

Wendy Suiter, Houston Dunleavy and Joshua Craig

Movers:

Jessica Millman, Solomon Thomas, Malcolm Whittaker

This

documentation is intended to, amongst other things, provide practical

insights that might be of use to practitioners attempting similar

projects or who would like to know more about working with the

technology.

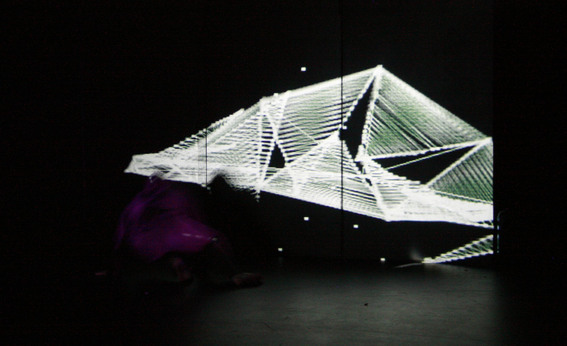

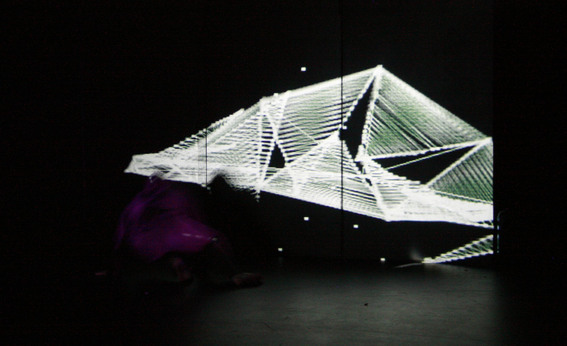

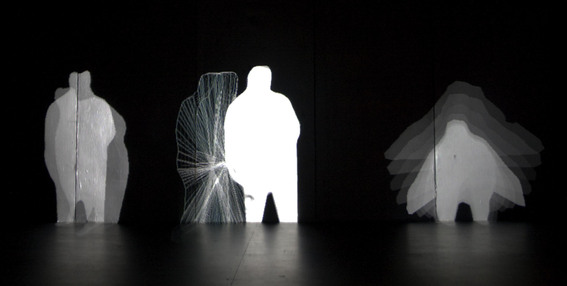

Solomon Thomas in Scene 2

Solomon Thomas in Scene 2

What is

feedback physically?

For the

2010 development feedback consists of a stage approx 5m x 3m,

backed by flats approx 5m x 2.4m. Stage and flats are painted black.

A

projector is located in the centre of the seating bank. The projector

lens height is roughly equivalent to performer head height onstage.

The projector beam is focused so that its bottom edge is aligned with

the front edge of the stage, and its width is the same width as the

flats. It covers the entire movement area. The projector is high

quality but otherwise has no special features.

A camera

is fixed on top of the projector. It is focused so that its view is

precisely aligned with the projector beam. The camera sees exactly

what the projector projects, from very nearly the same position. The

camera is a USB camera selected for it's extremely fast image

processing - there is no lag between real life and the image on the

computer.

Both

camera and projector are connected to a PC laptop. The laptop is

running a custom program using vvvv. There is a second laptop

networked to the first and connected to a sound system.

On

either side of the stage theatre lights are mounted on floor stands.

Each is coloured with Lee high temperature colour filter #181 - Congo

Blue. Congo blue lets very little visible light through, less than

1%. With power to these lights also reduced (to around 40%) the stage

appears nearly totally dark. Each light is of the type known as a

profile, and is focused so that its beam is shuttered off the flats

and the floor. They do hit the opposite wall but with the dark colour

and low power this is not a distraction. The lights are positioned so

the total effect is that they illuminate the volume of air in front

of the flats, but not the flats or floor.

The

final physical element is a light filter in front of the camera. This

filter is made out of several layers of the #181 colour material.

The #181

filter blocks most visible light, but passes infrared light through.

The theatre lights, based on filament technology emit infrared light,

along with much heat and visible light. The camera has been modified

so it can see both visible and infrared light, but the filter in

front of it only allows infrared light through. The projector

however, with it's complicated lens system and discharge lamp, emits

virtually no infrared light. In this way the projector light doesn't

contaminate the infrared image and the theatre light doesn't

contaminate the visible image.

When a

person walks onstage they are illuminated with the infrared light.

Because the flats and floor are not illuminated the person appears as

white on a black background to the camera, isolating their position

and shape onstage. The projector light, as it is only in the visible

spectrum, is not seen by the camera and does not interfere with the

camera taking an image of the person onstage.

The

computer can then process the camera image. From the silhouette it

calculates their location within the image, their 2D outline, their

width and height and their rate of change over time. This information

is sent to different algorithms which in turn feed the projector and

sound system. This output varies according to specific rules and

behaviours set up for each scene of the showing.

Note:

This form of tracking system is based on a thresholding logic, in a

similar manner to green screen effects used in filmmaking. An

alternative to lighting the performer is to only light the floor and

wall and instead track the performer as a black silhouette on a white

background. I chose not to do this as it would have been difficult to

get a consistent tone on the floor.

Another

tracking method is background subtraction. In this system a still

image is taken of the empty performing area. Anyone entering this

area afterwards is seen because the current image is compared to the

previously taken empty area image - whereever pixels have changed

there must be a performer. However if a change in ambient lighting

occurs the current image may be so different from the stored image

that the entire area is registered as changed pixels.

The

reason I chose thresholding is because it can deal with changing

lighting conditions by varying exposure and threshold level from

software, either automatically or by taking data from the lighting

control system. I have aspirations of integrating my tracking

projection with traditional lighting rigs so I needed a more robust

method than background subtraction in this instance. If you are

considering using tracking technology I highly recommend you

investigate both.

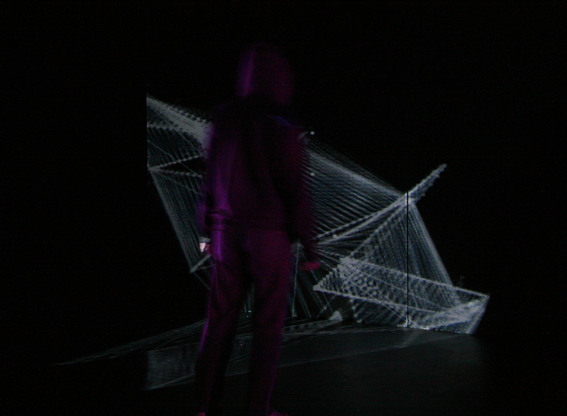

Solomon Thomas in scene 3

Solomon Thomas in scene 3

What is

feedback trying to achieve?

Feedback

is constructed, conceptually, around the idea of placing humans into

a feedback loop with machines. Both humans and machines are decision

makers within the loop. The long term goal is to produce behaviours

that are both emergent and accessible.

Emergence

is where complex output is created by relatively simple input,

however this is a somewhat subjective phenomenon. For feedback

the term emergence has a number of connotations: it represents an

effective, efficient algorithmic relationship in the sense that it is

more perfectly designed. It also often indicates that the algorithm

is an effective embodiment of the performer, reacting 'naturally' to

smaller, somatic movements (when that is an objective of the scene)

Creating

accessible behaviours simply means creating behaviours that hold

interest for viewers. It's important, if a little uncool, to

acknowledge accessibility when creating intensely technical works. I

unashamedly want feedback to go places in the future and so a

reasonable amount of consideration needs to be given to viewer

experience at all stages of the process. This accessibility is

manifest in the need for scenes to have a dynamic/shape. To go, in

some way, from A to B.

In 2010

the feedback loop functions

as follows: The mover moves onstage, the camera picks up their

movement and sends an image to the computer. The computer interprets

the behaviour as visuals and audio according to algorithms set for

each scene. The mover then reacts to the visuals and audio creating

the next frame of input.

For this

development there are four scenes. Each experiments with different

algorithmic relationships inside the loop. These relationships vary

from linear to abstract. I.E in some scenes it is obvious how the

performer affects the virtual environment, whilst in others it is

more subtle, to the point in scene 4 that it is unclear if they are

having an effect at all.

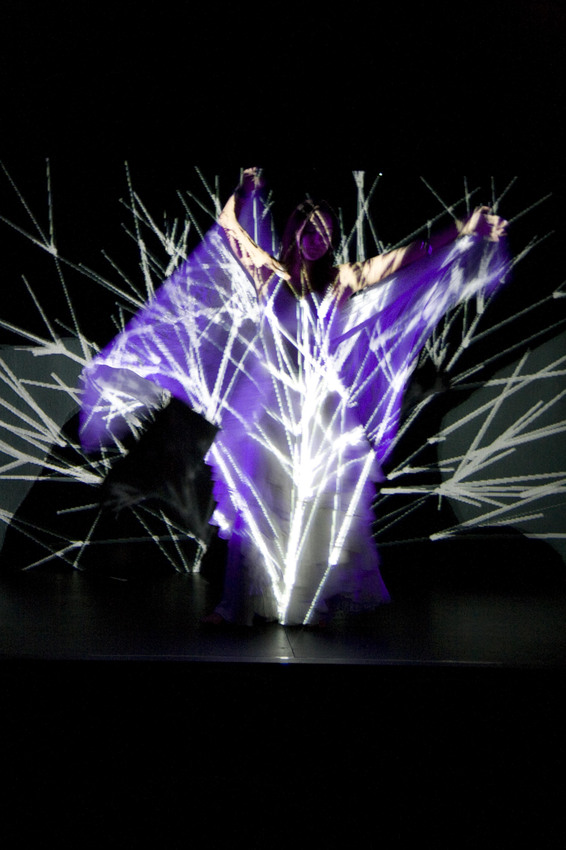

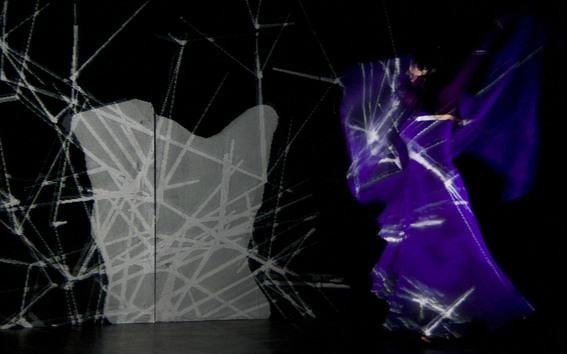

Jessica Millman in scene 1

Jessica Millman in scene 1

Where

did feedback

come from?

Feedback

originally comes out of the software I developed during my Masters in

Theatre at the University of Wollongong. At that point I was trying

to create a tool that would unlock the potential of digital

projectors in traditional lighting designs. The idea was to create a

system that allowed you to draw light directly on an actor with a

physical interface rather than having to work with abstract ideas

like channel numbers and parameters. You could precisely light a

face, or just elements of a face, or even draw in false shadows, in

any colour the projector was capable of. The created image would then

stay on the actor wherever they moved within the projected area. It

could be saved so that it was later recalled by a standard lighting

control desk, along with normal lights, so it wouldn't put any extra

burden on stage managers or lighting operators. I built a working

prototype with two projectors and staged a short performance:

Everlasting Geometry.

I'd used

bits and pieces of the software on a number of projects since, but

knew I wanted more time to explore the new lighting possibilities

offered by this kind of system. I began making enquiries but it was

when I saw Chunky Moves Mortal

Engine that I realised

there could be an audience for this kind of work beyond lighting

designers and other techno types. Mortal

Engine derives some of it's

appeal as a dance show, but it is arguably a presentation on the

choreography of light. Up till that point I thought light couldn't

have an audience, it was a show that had an audience and the show

simply needed light. Seeing it motivated me to think big and put

myself in the shoes of a director rather than lighting designer. If I

ever wanted an audience that big to appreciate my work, as I now

believed they could, I'd need to put myself out there.

This new

found artistic impetus presented some questions: As an artist, what

was I offering? Why was light my chosen form of expression? What was

I hoping it could communicate to an audience?

My

answer: When I was starting out I often did the lighting for band

nights in pubs. I only had access to some basic equipment with a few

colours and the interface was usually a manual lighting console -

no memory, and no use for it because you weren't going to see a

rehearsal anyway. However it was these gigs where I fell in love with

lighting. There is nothing like doing the lights for a band you've

never heard before in your life, but suddenly finding a moment where

everything syncs up. You feel the music building and the lights

build. You make the big moments big, the quiet moments beautiful.

It's like the architecture of this dingy pub comes to life and is

supporting the band, a sum greater than it's parts. And what I

realised after seeing Mortal

Engine is

that it's not just me,

everyone recognises it when it all comes together. We feel more than

human because the whole thing, the lights, the sound, the

gesamtkunstwerk,

embody our experience. It creates, briefly, a communal, tribal

connection that everyone can participate in if they choose. Lighting

is, for me, a form of universal communication.

Actually

doing it, having your hands on the buttons, feels like you are part

of a loop, part of the connection between the band and the music and

the audience and the technology. And you don't have to verbalise what

you are doing, it's just there without language, you know if the next

moment needs to be big or small or fast or slow but you don't need

words to describe it. It's like the you in your head that makes the

decisions is hardwired in there directly and you don't have to speak

through this big matrix of words and symbols. You just act.

The

experience I want to share with those who view my work is the

experience of being in that loop without spoken language or written

language or even body language. Feedback

is my first attempt to

bring that experience to an audience. And whilst dancers and

projectors may seem a long way from rock and roll I believe it's a

path that could get there.

Jessica Millman in scene 1

Jessica Millman in scene 1

What was

the process for the 2010 development?

Feedback

began

with an application to the Merrigong Theatre Development Program.

This was successful and Merrigong generously agreed to provide three

non-consecutive weeks in the Gordon theatre for creative development.

These weeks occurred in July and September, culminating in two

work-in-progress showings on September 8th

and 9th

2010.

I put a call out for contributors and

was lucky enough to get three composers and three movers involved.

After some initial meetings feedback was split into four

scenes of 10 - 15 minutes each. The team for each scene was free to

explore the concept of a feedback loop however they wished.

In the

end a wide variety of approaches and techniques were employed, an

ideal scenario for a first development. These included sample based

audio and video, generative audio and video, dynamical systems, AI's,

arbitrary and evolving relationships.

Scene 1

Visuals/Programming:

Toby Knyvett

Composer:

Wendy Suiter

Mover:

Jessica Millman

Scene 1

ended up having a very 'organic' feel, and explored an almost

sentimental algorithmic relationship between mover and machine.

The

sound employed a multi-speaker array arranged in a spiral through the

space. Wendy created four tracks of audio which were routed to the

eight speakers. Several layers of algorithms switched speakers on and

off according to a variation on the Fibonacci sequence. Some algorithms had

priority over others, for instance Jessica spinning onstage would

cause speakers to come on permanently. This gave the whole scene some

shape by ensuring we had more speakers on then off as time went on.

The actual tracks were made from site-specific sound Wendy had

recorded over a period of several months, most often from Thirroul

beach. Elements came and went from the soundtrack over time, adding

to this shape.

Jess

comes from a belly dancing background and the flowing movement style

she brought to the space worked beautifully. Jess also brought in a

veil which at first I was hesitant about. However once we tried it

onstage and I could see how Jess was using it to modify her shape it

became a vital part of the scene. I should take a moment to thank

Jess, Malcolm and Solomon for their patience and energy. I would

often ask them to get onstage and improvise for up to half an hour or

more whilst I pounded out code and rewired things.

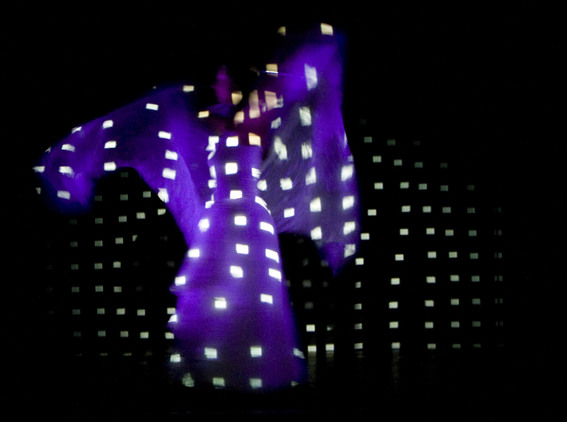

There

were two parts to the visuals in scene 1: The first was the 'dots',

which is a variation on the original prototype visual I developed and

had been using when showing people what the system could do. The

movement of the dots is based on a mathematical attractor.

Initially I to move away from the dots as I felt I'd already seen all

they could do, however I came back to them because they were just so

damn responsive to Jess's movements. The texture and movement was

such that over time I found I would see the dots rather than Jess,

I.E see the product of human movement, but not so much the human

body. By reducing the visibility of body language in the piece I felt

brought the viewer closer to seeing the loop itself rather than a

performative arrangement.

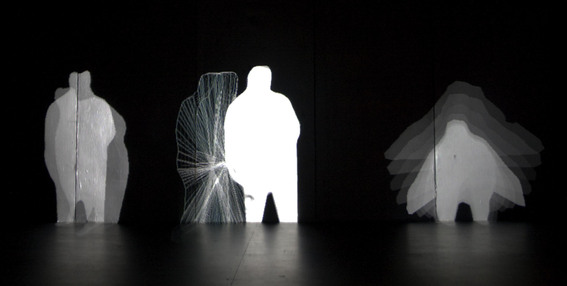

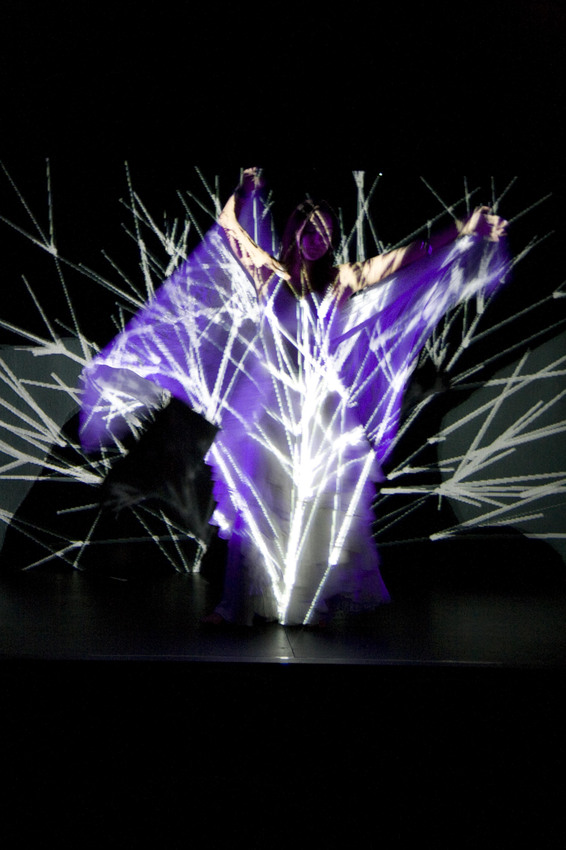

There

was a distinct shift where we moved to the second part of the

visuals, the dots disappear and a tree begins to grow from the bottom

of the projection area. The tree shape was based on a Lindenmayer

system and it's shape was seeded based on Jess's movements,

which meant no two trees would ever grow the same. In this section we

also see two 'shadows' on either side of Jess, these are modified

versions of her silhouette. After the tree has grown to its full

height it begins to break apart, shrinking to become hundreds of

dots, referencing the starting visual. However these dots, instead of

appearing in a grid, are disarrayed, still borrowing their positions

from the tree shape.

The move

from dots to tree, I hate to admit, simply occurred after a preset

time elapsed. For any future versions of this scene I would dearly

love to have this transition controlled by either the performer or

through biofeedback from the audience.

Solomon Thomas in scene 2

Solomon Thomas in scene 2

Scene

2

Visuals/Programming:

Toby Knyvett

Composer:

Houston Dunleavy

Mover:

Solomon Thomas

Scene 2

explored more literal relationships than Scene 1. In this scene a

Nintendo Wii Remote was used to give Solomon discrete control from

the stage. The concept was to create a sequencer that could record

several 'tracks' of audio and visuals, which could then be layered to

create new emergent landscapes/soundscapes.

Audio

was sample based. Based on Solomon's movement across the X-axis of

the camera (from side to side) different samples were triggered when

different zones of the stage were entered. Houston put together

several sets of samples, and the set used shifted throughout the

piece. Some of the samples Houston chose included a variety of short

and long percussive sequences along with an audio interpretation of

the wave form emitted by a star and some effects sounds (gun shots,

bells etc...). These samples could easily be retriggered and would

often be heard layering over each other.

Visually

the scene utilised four memory buffers that could record several

minutes of Solomon's movement. When Solomon held down the record

button on the remote his silhouette (and any sound it triggered)

would be recorded to the selected buffer. As soon as he let go of the

button the recording would play back in a loop, appearing to the

audience as a 'white shadow'. Any sound it triggered originally would

be triggered again as it moved. Using the remote Solomon could pause,

rewind, reverse and reposition his shadows, as well as adjust the

buffer and switch each shadow to a wireframe mode. Finally Solomon

could distort the shape of the shadows using his live movement.

What we

didn't get around to implementing was a quantising system so that

recordings on different layers would sync up. So as it was if you

recorded two shadows running around the stage, and one recording was

fractionally longer than the other, they would eventually go out of

sync. With a quantising system the time of the recordings could be

fractionally adjusted to ensure that recordings of very similar

length are trimmed to be the same length, and even potentially synced

to time properties of the audio samples.

Solomon Thomas in scene 3

Solomon Thomas in scene 3Scene 3

Visuals/Programming:

Toby Knyvett

Composer:

Joshua Craig

Mover:

Solomon Thomas

Scene 3

diverted from the first two in having a non-random decision making

machine. It employed a very simple AI to control an artificial

lifeform.

The goal

of the lifeform was to eat the shape of the mover. It was blind but

could 'feel' where the mover was onstage whenever they moved. The

faster they moved the more likely it was to extend a tentacle towards

them. If it could only detect small movements, not enough to give it

a clear reading on where to send a tentacle, it would instead

increase its total size and attempt to catch the mover that way. When

enough of its mass was touching the mover it would devour their

shape. A few moments later it would release but retain a shape

derived from the shape of the movers shadow. In this way the organism

evolved to resemble the mover over time, permanently taking some

amount of DNA from its meals each time it ate.

Audio

was generated in pure data. The same parameters that fed and

distorted the AI shape were sent to the PD patch via MIDI. In this

way the audio and visual expression were very strongly linked, to the

point that the sounds appeared to be the sounds of the organism

rather than the sounds of the mover moving, despite the latter being

closer to the truth.

Everything

the organism did was a result of the movers actions, just like the

algorithms in the other scenes. However the organism is clearly read

as a separate entity as opposed to the dots and tree from scene 1

which were strongly recognised as an extension of the movers body.

Scene 4

Visuals/Programming/Composer:

Toby Knyvett

Mover:

Malcolm Whittaker

Mover

(2nd

showing only): Solomon Thomas

Scene 4

runs in contrast to the others by purposefully obstructing the

relationship between the mover and the machine response. Technically

it still loops, but not in a way a viewer can easily identify. The

establishing and dissolving of repetitive patterns within the scene

compounds confusion further by providing the viewer with 'false

starts' where they believe a relationship is established.

The

vision consisted of 9 viewports displaying Betty

Boop for President,

a black and white film in the public domain. The viewport that

Malcolm stood in front of (and hence was projected on him) was the

only one that ran in real-time, the other 8 views would play any

frame out of the last hundred. The cartoon was divided into clips

between 5 and 20 seconds in lngth. Malcolm's movement was aggregated

as white noise, which would then drive the system in choosing when to

advance to the next clip and which frame the 8 delayed viewports were

showing.

The

audio algorithm was designed to trigger a drum machine via MIDI.

Every 8 bars a basic drum pattern was randomly generated according to

a Gaussian distribution. By default only a few of these beats would be

played. Malcolm's movement increased the probability that beats would

be played, until, if he moved fast enough, all drums would play on

all beats.

Malcolm's

movements explored a kind of non-dance. Instead of any kind of

virtuous movement he would parody movements from the cartoon,

themselves already caricatures of real movement. Most of the time he

would be imitating a movement from a clip that wasn't anywhere

onscreen so it was not immediately obvious that this was going on.

The

purpose of scene 4, in the work-in-progress showing at least, was to

evaluate the true value of providing 'supportive' relationships

between technology and human by taking that support away and playing

them in opposition instead. It also marked a significant departure

from our aesthetic by utilising the visual symbols present in the

cartoon.

Note:

I've avoided including scene 4 images until I can 100% confirm

the public domain status of Betty

Boop for President.

Jessica Millman in scene 1

Jessica Millman in scene 1What was

learnt from the work in progress showings (and post-show feedback

sessions)?

Overall

there was a positive response. Most people responded well to the

ideas presented within feedback and were keen to see it taken

further.

I think

people found scene 1 to be the most accessible and visually

arresting, many responding well to the dynamic changes within the

scene. Many came away with visual metaphors about fireflies and other

natural phenomenon which I feel is a comment on the expressiveness of

the visuals. Some felt scene 1 best embodied the concept of feedback

in terms of seeing a clear loop, particularly with the audio.

Scene 2

seemed to spark a lot of ideas about the potential of the technology.

Some said they felt the audio wasn't as responsive as scene 1, which

I believe is to do with the samples being triggered when the centre

of the silhouettes crossed a trigger, rather than their edges.

Because the centre changes as the shape changes it is harder to see a

consistent relationship between shadows and audio. There was also a

comment that one viewer believed there was less of a loop because

Solomon was facing upstage and watching the shadows rather than

facing the audience. In both cases, on a technical level, the reverse

is actually true - in a quantitative sense far more information was

sent that affected sound in scene 2, and arguably Solomon was better

able to participate in the loop by seeing what he was doing. I think

in both cases this points to a certain counter-intuitiveness about

some of these relationships, which I will elaborate further on in a

moment.

Scene 3

was widely recognised as being an interaction between two separate

entities, and the audio was praised for bringing the creature to

life. For me scene 3 is something I want to take much, much further.

Ideally I would like to see a dynamic that would begin with a

response to human expression, aka scene 1, but slowly splitting away

into separate human and machine agency, before perhaps merging again.

Scene 4

provoked a mixed response. Some people found it interesting, if

enigmatic, whilst others found it patronising. Some seemed to feel

that where they had 'gotten' what was going on in the other scenes,

scene 4 was cheating them by giving them nothing to 'get'. The viewer

response to scene 4 illustrated for me the value of the human-machine

relationship as a discrete element within the whole work.

In a

similar way to learning the secret behind a magic trick there seemed

to be a great deal of pleasure derived from seeing how each

relationship worked. But it was never how it really worked, its not

finding out about code or equipment or nuts and bolts. It's not the

relationship I see as creator and coder. Instead I think the viewer

sees a relationship on an intuitive, cause-and-effect level. And the

actual unfolding of it in front of them delivers some kind of

satisfaction, like solving a puzzle. However the viewer also has

expectations regarding what this relationship should be. There were

many comments about scene 2 and 4 that people 'wanted' to see sound

and vision sync up, that it would have been a stronger experience for

them if it had. This is also evidenced by some of the negative

reaction to scene 4, after the expectation was established of certain

relationships in prior scenes that scene 4 failed to deliver on.

So what

might these relationships communicate? This is still an area of

exploration for me, but I'm finding some parallels with lighting

design which is, after all, where this whole process started. I

believe the algorithmic human/machine relationships are political

relationships. They are commentaries on where power rests in the

performative environment. The organic relationship in scene 1 speaks

strongly of 'natural' power in the body. Scene 2, with its sampled

shadows, gave power to Solomon as a decision making agent - we see

a picture that Solomon has consciously arranged. Scene 3 also gave

power to a decision maker but began to localise that power in another

entity. Scene 4 took the power away from the human completely, giving

it instead to an arbitrary omnipresent machine (rather than an

isolated entity-machine as in scene 3).

Precisely

shaping the arrangement of apparent power within feedback will

be a vital part of its next development.

In terms

of the viewers themselves I observed a divide between those who were

frustrated by not being able to see the dancer, and those who never

even thought it was an issue. At first I thought this may be about

expectations regarding dance performance and a privileging of the

virtuous body, in the same way written text is often said to be

privileged in dramatic theatre. However I think it also may be to do

with an intuitive rejection of the feedback loop itself, or some

aspect of it. I need to think more on this but certainly it is a

factor to keep in mind for future development.

For me

much of the viewer response resonated quite strongly with my own

feelings on feedback, so one of the most valuable things to

come out of the showings was a validation of my own view of the work.

Jessica Millman in scene 1

Jessica Millman in scene 1

Questions

I now know the answer to:

Is

feedback a dance work?

No.

Physical movement is a vital form of input in feedback, but I

think the language and traditions of dance are something that would

cloud feedback as a whole work if they were to become a major

element. I do think getting the input of a choreographer is vital for

taking feedback to its next stage. I'd love to bring in an

'expert mover' who could help the other participants find a greater

range of physical expression in their interactions.

Is

feedback a theatre work?

No. For

me theatre is distinguished as work that presents ideas in language

and asks us to consider those ideas. What I want, and it's a big

want, is for language to be largely stripped out of feedback

in an attempt to communicate via.... whatever it is that is left when

you take away language. I can't describe it well yet. I see it in the

dots from scene 1. The person moves, they extend their arm, but we

don't see an arm and all the body language associated with an arm. We

just see the dots moving, but we know they are human because it's

still a human movement.

This is

a difficult decision. The clips in scene 4 are extremely attractive

to me from a visual perspective, and I will certainly revisit them at

some point, but for now they are too loaded with symbols and

language. I think feedback needs to remain true to my original

(and admittedly grand) idea, that there is some kind of euphoric

understanding to be found as a participant in a feedback loop. By

stripping away the distractions of higher, symbol based communication

I believe I can more effectively share my base,

Is

feedback a performance?

No. And

yes. The work-in-progress happened in a theatre and ran for 50

minutes. And I think the version of feedback that I'm

currently making funding applications for will do the same. And when

the next development is over I want to take it to festivals and

venues and show it in a performance format. I think this is simply

because I have a background working on performances and so I

understand how to put work on in these spaces. I think feedback

could also work in an installation format and I'm not ruling out

going that direction in the future. So I think the answer is that its

entirely subjective as to whether feedback is a performance or

not, I only know that its an expansion of my practice and so it hangs

on the same framework as my previous output.

Jessica Millman in scene 1

Jessica Millman in scene 1

What

does the future hold?

Lots

more of what we just began to look at in scene 3. A decision making

algorithm that can be as expressive as the dynamical systems

(attractors) used in Scene 1.

A

stronger link between the scenes overall, but not going so far as to

start thinking of it as a narrative.

Some way

for the movers to see what the vision is doing onstage without having

to face the back wall.

A high quality video camera to record the documentation.

A

biometric sensor worn by viewers. This signal would mediates the data

coming from the stage allowing the dynamic/intensity of the loop to

be controlled through some intrinsic value coming directly from the

viewer. Not only would this literally put viewers into the loop but

it would allow a 'natural' method for shaping the piece, rather than

relying on timed changes or other arbitrary control.

Jessica Millman in scene 1

Jessica Millman in scene 1

When

feedback is complete I hope to put the entire video of the

2010 September development online in order to complete the

documentation. However in the meantime find some excerpts here

Questions

and responses are always welcome.

I'd like to say a big thankyou to:

Merrigong Theatre Company for supporting my work.

The

Faculty of Creative Arts in the University of Wollongong for helping me realise that this was possible.

The

vvvv.org community for making this possible.